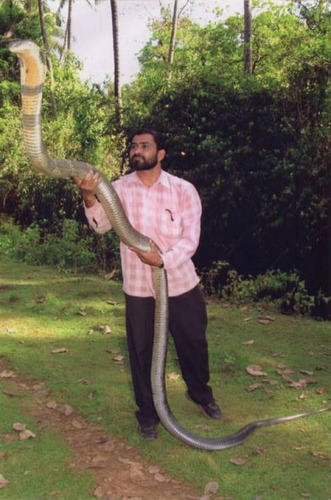

Mr Sreenath with the King Cobra he captured on 07 March '09 from Aralam Farm, Kannur, Kerala

PART-1

With due apologies to the likes of Romulus Whitaker, Brady Barr, Jeff Corwin and Steve Irwin, snakes were never too popular with the average person. Yet, there is a universal fascination for these creatures, albeit cloaked in loathing and dread, the reason why the aforesaid gentlemen succeed in popping up on primetime TV. It also needs to be said with great respect that these herpetologists have done a great job in bringing environment related issues to the layman’s living room.

My home state of Kerala in South India has more that a fair share of the lethal ones. The spectacled cobra, Russell’s viper, saw scaled viper and the deadly banded krait lead the pack. Some parts of the rainforest are home to the elusive king cobra, the largest venomous snake in the world, one live specimen measuring almost eighteen feet, as its keeper told me at the Trivandrum zoo in the 1980s. He could as well have claimed it to be thirty feet long, since no one would step in with a measuring tape. Such was its fearsome deep hiss, hood raised tall enough to look me in the eye from behind the glass partition.

In the seventies, our household had a live-in cook named Ammu. At the age of fifty, she had no living relatives and had chosen to be a spinster. She was indeed a very good cook if she put her mind to it. When she went on leave, she visited temples, oracles and shamans and came back with all sorts of strange stories, amulets and magic powders. She lovingly placed the charms in hemispheric coconut shells and buried them at various strategic points around the garden and especially outside the window of her ground floor bedroom. She firmly believed that this would save us all from evil eyes and bad spirits. It was generally agreed by the grownups that all of Ammu’s troubles came from her long spinsterhood. My dads’ elderly driver Khan Sahib was of the secret opinion that Ammu was still looking for her man and warned Chandran, the office boy not to step over any of her buried stuff.

Ammu was the daughter of migrant farmers who had settled on forest lands in the foothills of Western Ghat Mountains in the 1930s. Theirs is a blood and sweat story of wrestling with fertile yet wild land, fighting off beasts and suffering long stints of strange forest illnesses. Ammu had a large repertory of highland and woodland stories. There were also detailed reports on various temple festivals and pilgrimages. We children were forbidden to listen to her tales, generally classified by my parents as hocus-pocus. This taboo prompted us to sneak around the house to the small lean-to outside the kitchen during their afternoon siestas. Ammu would seat herself on a large jute grain bag and carefully prepare her betel nuts, leaf and lime paste for a good afternoon chew. We kids sat at a safe distance, not to be splattered by the red juice when Ammu’s stories reached their tempo.

Ammu had stories about logging stations, killer elephants, mahouts, floods, man-eating leopards, truck drivers, boat people, tea plantations, hunters armed with single barrel muzzleloaders and everything else that touched the lives of highland farmers. She told us of thunderstorms that lasted days, floods, disease and death. She also had a few country songs, more like ballads. One described men riding huge logs down swollen rivers during the monsoon. Another went on to tell the legend of Mallan Pillai, who tamed wild tuskers and was finally killed by one. It was all from another world and time and we listened, entirely captivated.

One of Ammu’s stories came from her own experience. She had an uncle named Balaraman who collected wild honey from the forest with his young nephews. Wild honey was always collected in sawn-off bamboo stems and sealed by a waxed wooden plug. During one such expedition, he was bitten on his scalp by a tree cobra. He lived barely long enough to climb down the huge tree and died on his favourite nephew’s lap. Ammu always cried when she told this story.

PART-2

Having never heard of a tree cobra, we often asked Ammu to describe it. Again and again, she insisted that it was not a big snake, not thicker than a woman’s finger, with a thin hood and lighter coloured bands. She insisted that it was known by the local names of ‘illi moorkhan’ and ‘komberi’. Later in life, I asked many snake charmers about the cobra that lived in the trees. Most said that there was indeed a ‘komberi’, but few had seen it. Those who claimed a sighting always gave contradicting descriptions. It was differently described as huge, green coloured, with the comb of a cockerel and so on. One confidently said that the ‘komberi’ was so vengeful and sure of its kill that it left the area only after seeing the smoke from the funeral pyre of its victim. It was indeed frightening and ghoulish.

Irulas are a famous snake catching tribe from Thiruvallur district in Tamilnadu. On a hot May morning in 1980, I came to know that a group of Irulas were catching snakes in the sprawling University Campus at Karyavattom, Trivandrum. It was only a thirty minute ride and I set out immediately on my friend’s old Jawa bike. It was a late Sunday afternoon during the summer holidays and the campus was deserted. I finally located a group of small dark men dressed in khaki shorts and tucked up lungis. They were relaxing under the low spreading branches of a cashew tree. There was a smell of burnt hair and a fair sized bandicoot rat (Bandicota bengalensis) was roasting over a fire. Irulas were expert rat catchers too, greatly valued by farmers of the rice paddies. It was a good working arrangement, with the Irulas keeping all the rats they caught and also the paddy recovered from the rat holes. Any snakes caught during the process were a bonus and would be later sold to snake charmers. No money was ever exchanged for their services.

The leader of the team was a wrinkled old man called Maari. Though he was a bit reluctant to talk in the beginning, he relaxed when he realised that I was not a policeman. In my best Tamil, I told him that I wanted information about snakes and that no one would know them like he did. I handed over my pack of Charminar cigarettes and was rewarded by a huge smile. A young boy was despatched to find a bottle of arrack, which I sponsored, and it was party time. Maari showed me half a dozen round plastic pots, mouths fastened by sack clothing and string, the day’s catch. There were half a dozen Russel’s vipers and an equal number of spectacled cobras. The prize catch was a black cobra, almost seven feet long, though Maari insisted that it was just an ordinary one, with just a change of colour. There was also a non-venomous sand boa with a rounded thick tail, making it look like having two heads. To my surprise, Maari informed me that they no more sold their snakes to charmers. Instead, they were bought for a good price by venom collectors. He also admitted that many of these venom dealers were private businessmen who had no licences from government bodies.

Maari handled the agitated, freshly caught snakes quite casually as he returned them to the pots. The Irulas never carried any antivenin and relied on their own herbal medicine which seemed to work, at least for them, despite the scepticism of allopathic doctors. Irulas getting killed by snakebite was almost unheard of. They were often seen hawking their medicines and charms at village fairs and temple festivals. Also, there were no tales of farmers being saved by Irula medicine.

An hour or so later, politely declining a choice piece of roasted bandicoot, I asked my pet question. Is there a ‘komberi’, and has he ever seen one? His eyes lit up. Relaxed by the potent arrack, he nodded slowly. Yes, once he caught one from the bamboo forests in Kodaikanal foothills. It had died before he could sell it. I asked him how it looked like and to my great excitement, his description matched Ammu’s, word for word. And yes, he had indeed caught it from a tree. When I rode away that evening, something made me trust him, though no zoologist or herpetologist had ever written anything authentic about a tree dwelling cobra.

PART-3

Another two years went by and along with three other friends, I was camping rough in the pine woods of Kodaikanal, the famous hill resort in Tamilnadu. We were befriended by a colourful character called Horseman Velu. Aged about sixty or more, he was the ‘daddy’ of all horsemen who operated around the Kodai lake. He could out drink most men and had great affinity for cannabis which seemed to have no effect on him. Velu appointed himself as our guide and we took an immediate liking to the old rascal.

For the next five days, Velu took us for the trek of our life. From Kodaikanal, we trekked to the villages of Kukkal, Manjampetti and Poompara. Trekking through Mathikettan Shola National Park, we met tribal chieftains who ruled forest lands as if the Indian Republic never existed. Churuli Chami Pillai was the chief of Poompara village and he had his own bodyguard complete with an antique Purdy twelve bore double barrel. We were the honoured guests of Kona Kotta Chami, the chief of Kaattu Kona tribe. Almost a week later, we came out of the wild, following the Pambar River, which flowed with a roar through deep narrow ravines cut steep into the rocks. We had walked right along the borders of Eravikulam National Park, home to Nilgiri Tahr, the endangered mountain goat. During the week we had been chased by wild bison, and stalked by packs of wild dogs. We finally ended up dirty, blistered and raw skinned on the highway to Munnar, where we flagged down a truck and bummed a ride to the extremely polluted Munnar town.

It was in the Mathikettan Shola National Park that I had my first clue about the ‘komberi’. The Shola forests have extensive bamboo clusters, home to the snake eating King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah). It was Velu who opened my eyes. The king cobra is the only snake that builds a nest and stands guard over the eggs. After a period of incubation, the eggs hatch almost simultaneously and the young ones have to fend for themselves. These hatchlings are about half a meter long, complete with a potent venom and tiny hood. To fit a few last pieces to the jigsaw, these baby kings are indeed banded and take to the trees soon after hatching to escape from all sorts of predators including their own kin. They stay in the trees till they are sufficiently large enough to hunt their traditional prey, meaning other snakes. While living in the trees, the baby kings definitely have enough venom to kill an adult male, as explained by Romulus Whitaker, the foremost authority on king cobras.

Gentlemen, Holmes has the honour of telling you that he has solved the longstanding mystery of the ‘komberi’ and the death of Ammu’s beloved uncle Balaraman, while collecting wild honey in typical king cobra country. Yes, he was definitely bitten by a baby king hiding in the branches of a tall forest tree.

Concluding Notes:

a. If anyone knows better, please write to me. I shall be happy to stand corrected.

b. In 1973, Ammu went away on one of her pilgrimages and was never seen again. May be she found her man.

c. A friend from Kodai tells me that in 1985, Horseman Velu was shot dead in the Kukkal woods by forest guards while resisting arrest on a poaching charge. Knowing him, it would have been easy for poachers to befriend Velu. He was a fine old man, right out of a Clint Eastwood movie or a Kazantzakis novel.

d. To the best of my knowledge, there have been no deaths attributed to the tree dwelling cobra during the last fifty years or so in South Kerala. Any breeding areas of king cobras in this region are also not reported.

e. Baby King Cobra on a tree branch; picture courtesy: Tlau Vanlalhrima, Aizwal, Mizoram.

Awesome read.. I enjoyed it.

Your narrative has a mistake, but your conclusion is very right. The mistake in your narrative is regarding the banded krait. The krait in Kerala is the common krait, which also has bands, but not so well defined. The Komberi is indeed the juvenile King Cobra and this snake has clear bands when young and could pass off as a banded krait too. The actual banded kraits are found up north. The juvenile Kings are very perky and as all young ones, are raring to show off and it is quite possible that Balaraman was bitten by one. Great whodunit.

Dear Narayan Das, thanks for visiting my blog and for your comment. I have seen a krait only twice in the wild. One was almost black and the other one was indeed banded. I have referred to the ‘banded krait’ because it is also called the ‘vellikkettan’ (meaning silver band) in pure Malayalam. I was quick to assume that the banded variety was native to Kerala since there was a local name for it. Your point is noted. Cheers.

Dear Prithvi, I came across another snake mystery and thought you should know. The link will take you there.

http://mazoomdaar.blogspot.com/2009/06/in-search-of-snake-demon.html

Thanks, NDR. I did visit Jay Mazoomdar’s blog and it was indeed a very good read that came from a fascinating quest. I would recommend it to all who would chase a wildlife mystery.

Excellent article, I read this article more than ten times again and again, reading more generates more interest.. You have mentioned there is no death attributed in the last 50 years from baby cobra’s bite. What about Balaraman?? Did he not die of a baby cobra bite??

Have you heard about naga mani (Cobra pearl) which has an intense brilliance and is said to be powerful and will ward off evil..

Can you give me some details about the king cobra held by Mr.Srinath in the top picture?

Dear Sriram, thank you for going through my blog. Now let me answer your questions as best as I can.

Ammu worked in our household in the early 1970s. She was already about 40 years old then. Her uncle Balaraman was killed when she was just a teenager. That should explain the fifty years in the article.

I am not an expert on gems and other precious stones, though I graduated with Geology as my main paper. But I can tell you with a great measure of certainty that Naga Mani is just another grandma’s tale. A fascinating one, though, this many headed snake with a magic sparkler on its hood. Take it no further.

The picture in the article is credited to a newspaper as mentioned. For more authentic info on Ophiophagus hannah, please see the link http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Cobra . Cheers.

Bulk of the first ten years of my life was spent in my grandparent’s farm; foothills of Nelliyampathy.

I grew up listening to the legend of this Komberi Moorkhan; it was said, once it bites a person, it goes up a tree and only comes down once it sees the smoke from the funeral pyre.

I have seen this snake. Legends aside, it is the bronze back tree snake.

The one that kills people has to be the baby king snake.